In Conversation with Alternative Ceramics Supply

(AB) Amelia Black

(CE) Claire Ellis

(GS) Georgia Stevenson

(SMS) Sarah Muir-Smith

What led you to start working with found or recycled materials? Was it a conscious decision or did it slowly manifest through your work?

CE: I was led there because of my interest in supply chains that began after learning about different kinds of exploitation as a kid. Also because of my desire to process my own materials and my love of experimentation which I carried over from my former career as a chef.

AB: Through my work as a designer, moving to more renewable materials has always been central to my professional life. However, when I moved to Australia in 2020, I got the opportunity to develop an R&D program for a ceramic manufacturer utilising industrial waste streams, which unlocked my love of ceramic chemistry and transformed my studio practice.

GS: Family friends gave me clay from their property, of which I explored a handful of ways I could use it – as a clay body (testing different firing temperatures), as a slip and as a glaze. I made some pieces and gifted them back, transformed by heat. From that point onwards I’ve been taking opportunities to collect byproduct, construction and demolition ‘waste’ or materials of sentimental value to test their application in ceramics. I was always curious about supply chains and where things came from, as well as why clays have different characteristics: I’d ask myself, what’s making the clay speckle, what gives it colour, and how are these properties a signifier of the place it came from?

SMS: My lightbulb moment was learning about early Japanese ceramics and how the “waste” materials of the time (wood ash, rice hulls) could make beautiful glazes. When finding out that wood ash is mostly calcium, I asked if it was the same calcium as in antacids and my mind was further blown to find out that chemically speaking, everything is made out of the same building blocks. Learning that materials from our environment can be used in ceramics was a pivotal moment, and led to a deep material investigation that now underpins my practice.

Bricks from Demolition in Collingwood

How would you define the term Alternative Ceramics Supply to somebody hearing about it for the first time?

We see Alternative Ceramics Supply (ACS) as an artist collective that disrupts the status quo in the ceramics community by exploring alternative ideas and materials. For us this platform is a way to challenge the assumption that the only way to work with clay is to use mined minerals. Together, we are advocating for the custodianship of materials rather than ownership, aiming to empower potters to look at the materials in their immediate environment (including local urban waste streams). We prioritise education, empowerment, transparency in supply chains, safety, and community building. Environmental, cultural and social responsibility in pottery is at the core of what we do.

There are four of you collaborating on this project, how did you come to form this collective?

It happened pretty organically! We all live within a 15 minute radius and met each other through Instagram and exhibition openings around Melbourne. We naturally became friends due to our pretty niche shared interests and work in alternative materials. Our ongoing group chat is equal parts troubleshooting, encouragement, nerdy links about rock or environment-related things and podcast recommendations for long studio sessions.

Georgia had the idea of Bulk Buy brewing in her mind and sent through an email asking if anyone wanted to help organise it. When we were filling out the application form we decided to apply as an artist collective under the name Alternative Ceramics Supply. It became exciting to imagine doing more projects and events together to draw on everyone’s individual and complementary skill sets.

How does the rich context and technique of working with such materials impact the outcome of your practice?

Working with local and abundant mineral sources is nothing new. In processing materials ourselves, we are following in a long lineage of ceramic tradition. Rather than relying solely on traditional sources for our materials, we looked to our urban and industrial landscape.

By building relationships with the sources of our materials, we can open up a new connection with supply chains and the past lives of our materials. By following the journey of preparing materials from raw state to something ready to work with, you become intimately aware of how precious every gram is!

Exploring each material’s provenance has helped us respect and understand their story, and the desire to centre ourselves has diminished. Rather than imposing our ideas onto the materials, we’ve learnt to work in more of a dialogue. The qualities and character inherent to the materials become even more apparent. Also because our focus is on the materials rather than the outcome, our ways of making have adjusted and we’ve learnt to embrace change along the journey. For example, in some cases moving away from wheel throwing and exploring new techniques like slip casting and press moulding.

Amelia Black

Claire Ellis

Is there a particular project(s) that was/were pivotal in your practice? What has led to material focused work?

I became interested in ceramics as a sustainable practice during my design BA at Camberwell College of Arts. It was the first time I really began to comprehend how objects were being made in a globalised world and I was terrified. Although I now realise it was a bit romanticised, ceramics seemed to offer a way out because it was possible to source one’s materials.

Soon after, during a student exchange programme at Les Beaux-Arts in Marseille, an artist called Delphine Wibaux gifted a piece of clay she’d found to me. That little piece of earth made such an impact that I devoted my semester there to collecting clay samples from across the region. When I realised what diversity of results can come from clays found in one area there was no going back. But it wasn’t until I moved to Stoke-on-Trent and went to Clay College that I was able to really refine this knowledge.

Sarah Muir-Smith

Georgia Stevenson

In the UK there is little education to the provenance of materials and their impact on our environment. How does this compare with Australia?

It’s funny you say that because coming from Australia, we often look to the UK as an example of a much more transparent material supply chain – especially because it seems like there is still a very active tradition of semi-industrial ceramics.

That said, it seems common for potters and ceramicists all over the world to feel like they don’t know enough or haven’t been trained in materials… so many of us are self-taught or come from a background of working in community ceramic studios where there are no formal curriculums (we all did!). It isn’t until you start mixing your own glazes that you start to wonder about all those white powders, where they come from and what they do chemically.

Amelia and Claire are part of a collective called Clay Matters and are actively working to break down the barriers for ceramicists to learn more about their materials, where they come from and their impact on the environment. It’s called the Material Provenance Project, and it will formally launch in May but readers can learn more about it and get involved here.

Is it essential to work with local materials rather than purchased ones? If so, how come?

While not essential, working with local materials can be valuable for several reasons and even small changes towards maintaining circularity in studios can have a significant positive impact. It involves looking at the community and local businesses for the untapped material potential that can be upcycled. For ACS, the use of local second-life materials aligns with our values and goals, making it a central principle in our work.

We think the concept of "local" extends beyond just digging up clay. If you’re taking materials from nature, it's important to consider the ecosystems and traditional owners of the land. Local might not always cause the least harm.

Using local materials can be valuable on a personal and artistic level as well as reducing the carbon emissions from your practice. It fosters a stronger connection to the materials, brings a sense of ownership to the creative process, encourages the conscientious use of resources, and promotes recycling and remaking rather than wasteful disposal..

It is clear using recycled materials, especially byproducts of industry, is at the heart of your project but given there is a variety of products to choose from; brick and tile rubble, heritage glass, concrete chunks and others, what factors influence your choice?

The first factor is whether the material is abundant, available in our immediate environment, and applicable for use in ceramics (ie, not organic matter that will simply burn out). After that, we check that the material isn’t harmful to the environment or humans working with it. Otherwise, we sought the broadest range of chemical compositions, to allow us to substitute as many traditional glaze ingredients for second-life ones as possible. Where feasible, and particularly with industry byproducts, it’s useful to find materials as close to the state that you require them to reduce unnecessary resources in processing them.

You had to learn multiple approaches to processing materials, how has this labor-intensive journey impacted your relationship with making at scale?

Attempting to process all those materials ourselves highlighted the need to find other people to partner with who have access to larger-scale equipment. Even with a rock crusher in our toolkit, it required a huge amount of manual labour to get everything ready to be used in studio ceramics (like hand-sieving out every grade of material).

This way of working deepened our connection to the materials, but the time and physical labour were limiting factors in how much reach we could have and how much material we could sell to other potters.

Despite these challenges of scaling up, Bulk Buy demonstrated the potential of second-life materials. We hope that it will lead to a broader industry shift towards normalising their use that would be more accessible for all.

Do you feel that all of us as makers need to transition to using local and recycled materials?

It can be easy to assume that local or recycled materials are good and imported raw materials are bad… but it’s not that simple. Things like fritted materials can give us access to stable, safe chemistry that wouldn't be possible otherwise, while some recycled materials can be quite hazardous.

So what we would advocate for instead is an informed culture of awareness of our materials. We advocate for ceramicists to understand the impact of their choices and to make educated decisions about what they use in their studios. Our materials are tied to massive geo-political systems, and by understanding this landscape we can help push for real global change. For example, we use silica in almost every aspect of ceramics - this is the same material used to fabricate the semiconductors powering the device you’re reading this interview on. It’s all connected! Plus, it can be incredibly empowering to replace a purchased material with one that you make yourself.

Taking the time to learn about materials and making a more informed choice is the way to go - and will allow you to establish a more resilient studio practice that can weather inevitable changes to ceramic supply chains.

Last year you organized ‘Bulk Buy’ at Testing Grounds Emporium in Melbourne, Australia. Could you describe the project for the readers? What was the outcome?

Bulk Buy was an exhibition and pop-up shop for ceramicists. We tried to imagine what a pottery supplies shop of the future could look like. Surprisingly, this invited in a lot of people outside the industry but were interested to see what we were doing… such as architects, academics, and tourists.

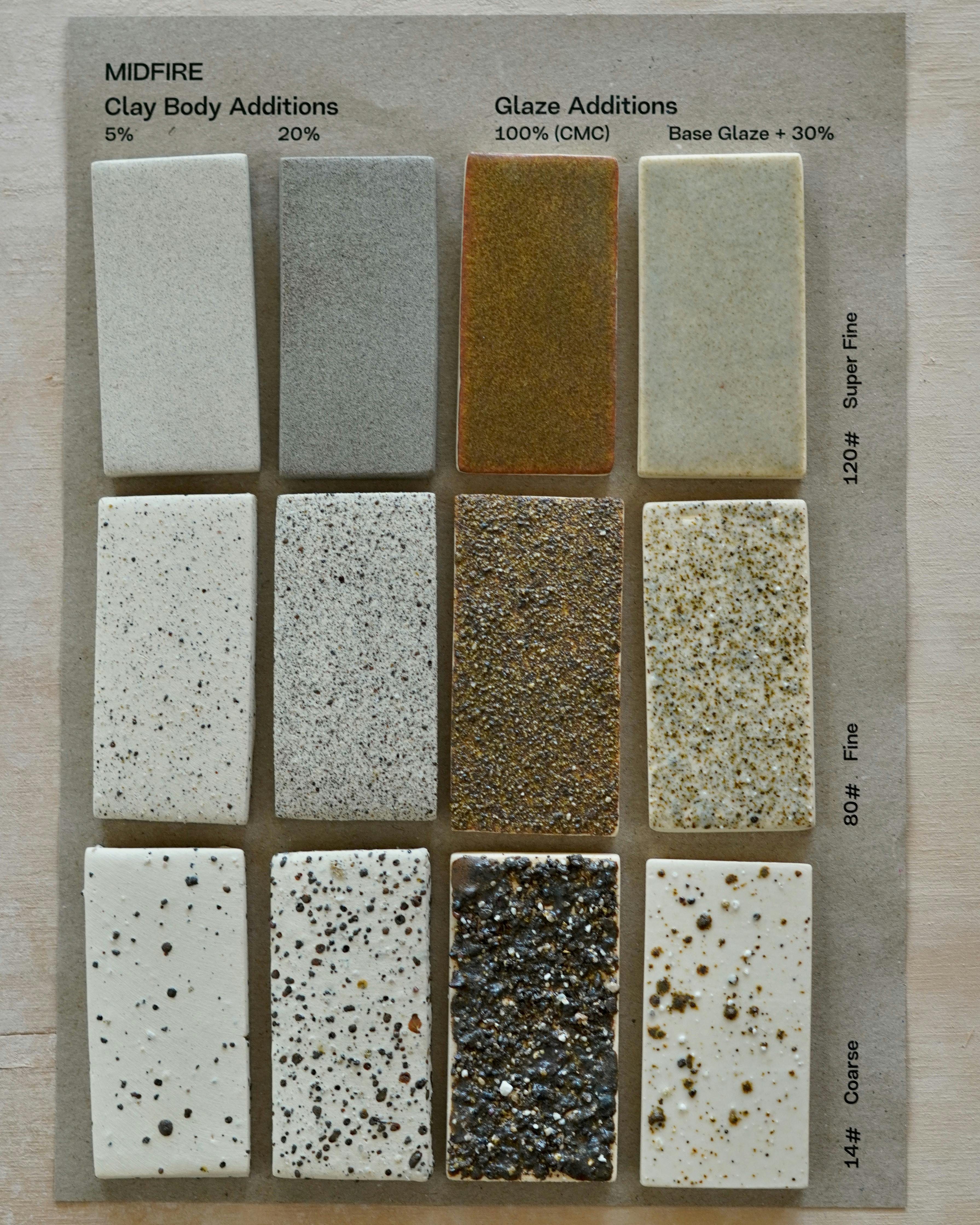

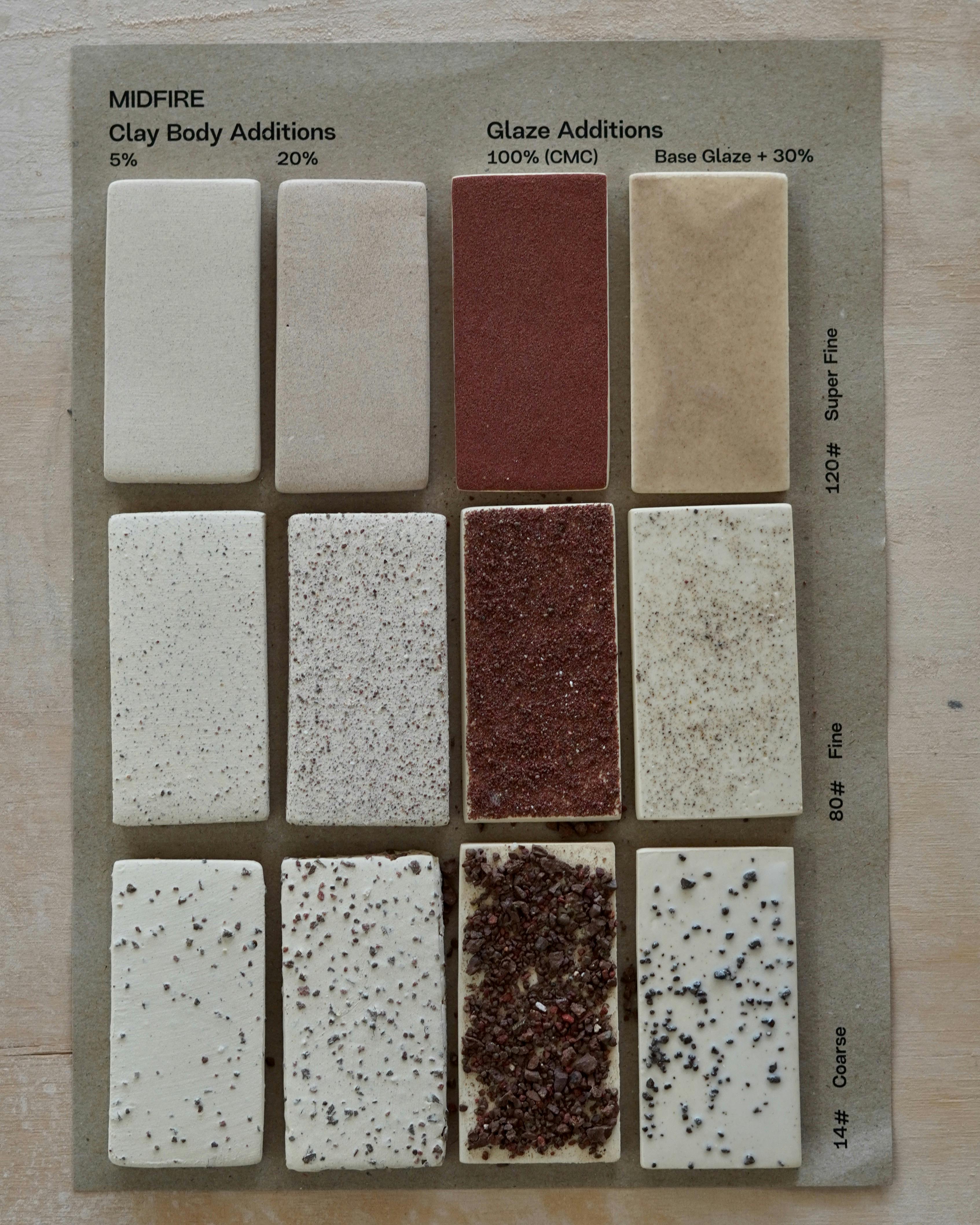

The project involved collecting ten second-life materials from around Melbourne, processing and testing them for use in clay bodies and glazes. We showcased test tiles for each material batch with detailed information on provenance, safety, and chemical composition. Looking to Revival Projects as inspiration, we introduced an alternative consumerism model focused on the transfer of custody rather than ownership. Our packaging was plastic-free and featured the labels of our dreams with the location they were gathered, the name of the indigenous group whose land the materials came from and chemical composition. We used icons to denote that the material was recycled and acquired through ethical labour, as well as to show requirements for safe handling and responsible disposal.

The event itself was an absolute can of worms, with so many lines of inquiry to follow up. It was good to start the conversation with other potters, and also to speculate ‘what is a better way to do this’? The pop-up shop was as much about conversation and connection as the materials, but that said, we’re pretty proud of the fact we sold and transferred the custody of over 40kg of second-life materials.

What methods do you follow when collecting and testing materials? Please share any practical tips such as steps you can take when testing clays and glazes. If there is one piece of beginner advice you could give, what would it be?

Our general approach is:

Safety first! Check if the material is safe to use by researching it, and get geared up with any necessary PPE. Ensure your kiln is ventilated and protect it by using drip trays and saggars if you think your material might fume.

Read up on the materials before you start working with them. Such as checking the recommended calcining temp for all your materials, some rocks are easier to crush when they are calcined to 980°C but other materials like oyster shells need to be kept under 550°C otherwise they turn into calcium oxide (aka quick lime).

Crush and process the largest batch that you can manage, separate into different mesh sizes and do melt tests for each

Document everything and be consistent! Take plenty of before and after photos, label and date all your test tiles, and keep handwritten notes or spreadsheets.

Our biggest piece of advice for a beginner would be to find your community! Having a teacher/mentor/group that you can ask questions, either in person or online is incredibly helpful. It’s amazing how many problems you can solve with a healthy group chat.

Amelia Black - Claire Ellis - Georgia Stevenson - Sarah Muir-Smith

Breaking Ground

Photo credits :

Motherock by Lille Thompson

In Plain Sight by Tatanja Ross

Materiality of Melbourne by Annika Kafcaloudis Bulk Buy by Michael Pham

Triple Cooked and Material Studies by Henry Trumble courtesy of Craft Victoria

All other photos courtesy of the artists