In Conversation with Rosanna Martin

Describe the role materials play in your work, particularly in terms of their locality and place-making.

My childhood was spent making weekly visits to my grandparents’ sheep farm, where we would walk across the fields and down to the site of a former brickworks. The brickworks existed from 1891 – 1907 on the foreshore of a tributary of the River Fal. The brick makers dug clay from the river bed and used it to make and fire bricks in beehive kilns before sending the bricks off on boats to build houses in Truro and Falmouth. The clay used had settled there after being spilt out of the china clay extraction pits on the western side of St Austell. Hundreds of thousands of tons of china clay and mica was lost to rivers due to rudimentary refining processes. It silted up the river bed, layering on top of mud to create a bright white clay flat when the tide was out that sparkled with mica in the sunlight. As children, we would run, skate and slide across this mud as if our feet were ice skates, and we would swim in the river channels, making chutes in the clay banks and splashing into the milky water.

This early exposure to a very specific waste material has informed my practice to a great extent, unconsciously, I think, for a while, but this became much more conscious over the past decade. Learning more about how the clay had come to be where it was, and the processes involved in the transformation of material fascinates me. The impact the china clay extraction industry has had on the landscape in Cornwall is phenomenal, and the new landscapes that this human activity has created are beguiling and somehow full of potential.

How does working with materials rich in context and labor impact the outcome of your practice? How does the process of collecting and processing these materials affect your work?

I returned to Cornwall in 2017, after a few years of living and working in London. I was burnt out and seeking grounded connection. One of the first things I did when I came home, was return to the clay river that I had explored as a child, and scooped out handfuls of the stuff. I didn’t know what I was going to make with it but that didn’t matter - even just the process of collecting this clay felt good for my body, in its immediacy of nostalgia, smells and immersion. Over the next few years, I gradually began to weave in to my practice things I was learning about the heritage and labour of brick making in Cornwall - how the bricks were made from this clay, and how the china clay extraction and brick making industry were all so inextricably linked to the deep geological time of this landscape, and the current economic state of the area. I still find it utterly beguiling and full of wonder that a handful of clay can tell so many stories and offer a portal to understand different ways of life and connection to land.

Materiality and the craft processes involved in understanding a material play a huge role in creating opportunities for connection between people and landscape. A lot of the ex-extraction land where I work is generally off-limits to the public for safety reasons. This can make the landscape feel wild, ominous and alienating. With the wildness comes an opportunity for plant and animal life to flourish, and the landscape that has been made out of waste quartz sand from the industry is now creating new ecosystems and habitats. Learning about how the materials came to be in the place they are provides insight and understanding, but being able to actually make something out of and transform those clay materials into fired glazed ceramic using materials that have all been gathered from within walking distance generates real wonder.

Is it essential to work with local materials rather than purchased ones?

For me, it has become essential on some level. I have gathered clay from other sites across Cornwall, but my preference is to use clays that have been deemed as waste by the extraction industry. I find the connection that this gives me to the locality, and the meaning or sentimentality embedded within that too hard to resist! I have always enjoyed being in dialogue with the materials that I choose to use, and so I also love the necessary testing, and process of understanding a material that takes place over time when one is working with materials collected locally. Recently I have been making pieces out of materials that I can find within walking distance from the studio site, or sourcing other waste materials from local industries, such as wood ash from our local beach sauna, or granite dust from the saw at another nearby quarry.

There are limitations to this way of working, in terms of making techniques and colours. I enjoy working creatively within those limitations, but I am not a total purest!

Your practice encompasses both material and historical research, inviting the public to engage with clay in a deeper and more informed way. What role does education play in your project?

My practice has always involved an element of educational participatory work and I believe engaging with and creating communities of people around a shared interest is an incredibly important way of being in the world. Working together provides an opportunity for shared learning and pooling of knowledge, often in an intergenerational space, which allows openness and creates space for discussion. I find that when people are making with materials they have collected themselves from the local landscape, there is so much to talk about. Gaining the connection with that material provides an opportunity to talk about some of the more difficult and complex themes around our use of materials, their importance, and how we can challenge anthropocentric thought by deepening our understanding of materials and where they have come from.

The communal and educational aspects of your work seem to naturally tie together various sides of making and production into a coherent narrative. Do you find that either of these aspects leads the project, or is it more of an organic process? What role does research play within your practice?

Different aspects will lead my practice forward at different times. Since 2018 I have been leasing a site of disused china clay extraction land from Imerys. On this site I have facilitated various projects - primarily Brickfield, a participatory collective brick making project, as well as running wood-firing courses, hosting researchers, artists, and other local ceramicists to run their own activities. The site is also a primary research site for the PhD I am currently undertaking at Falmouth University. The outcomes of these different activities can vary wildly, from bricks, to sculptural ceramics, to research papers. The thing that brings them all together are the materials that everyone engages and transforms in some way with when they are on site.

Is there a particular project that was pivotal in your practice? What led you to work in this community-centered, material-focused way?

Ever since I graduated from my ceramics degree in 2008 I have been part of projects that have enabled me to share my skills with others. Each project, or organisation that I worked for over the years embedded the importance and vitality that working with others and sharing your practice can give. I have always found it fulfilling, but often felt a level of separation between my own ceramics practice and the activities I was facilitating. When I returned to Cornwall after working a number of different jobs in London, I wanted to set something up where I could commit to working from one place, and so I founded Brickworks, an open access ceramics studio in Penryn that ran from 2017-2020. This studio was a pivotal moment in me learning even more about the importance that making can play in people's lives, though there was still a degree of separation between my own sculptural work which I made in a different studio, and what I was hosting at Brickworks. It wasn’t until I was invited to run a workshop as part of Groundwork, a programme of contemporary art in Cornwall organised by CAST, that my focus turned to brick making, which planted the seed for the Brickfield project, following which my practice and my work with others became inextricably linked.

Your ongoing project, Brickfield, set in a disused china clay quarry near St Austell, Cornwall, stands out. What role did the locality and historical context of Cornwall play in the development of this work? What are your hopes for this project in the future?

The locality and the historical and industrial context of this site played an integral role in the development of this project. Research into the heritage of brick making in Cornwall allowed early ideas to develop. Running our first weekend brick making workshop at the site of the former brickworks on my grandparents farm was hugely insightful in that we saw the power that the process of gathering clay directly from the land, and forming it into bricks could offer people.

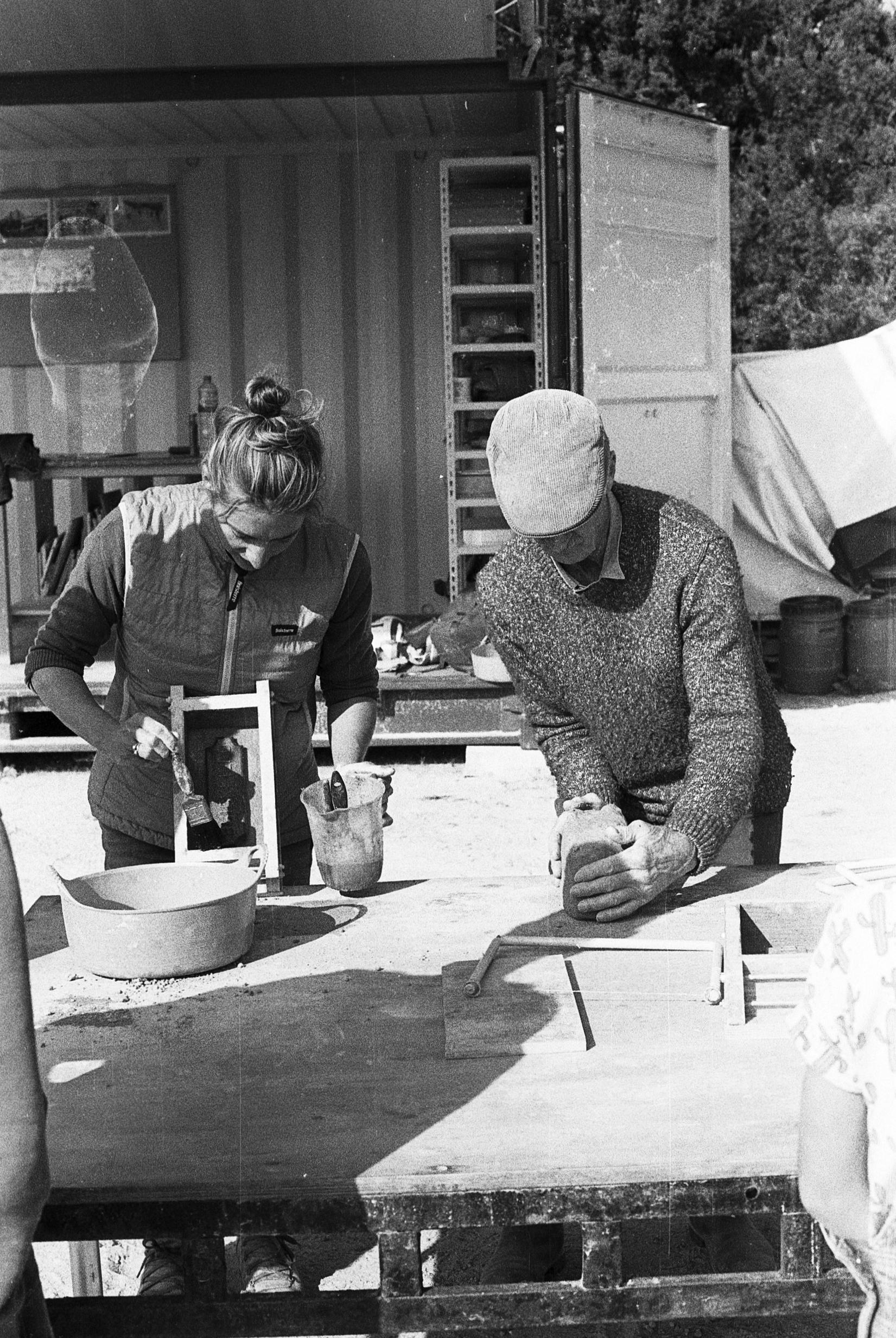

In 2019, after our first season of brick making from the disused quarry, we ran a series of workshops in local village halls. At one of these we met John Osborne, a brick maker in his early years and the last man to fire the last working beehive kiln in Cornwall. He hadn’t made a brick in 50 years, but the embodied knowledge embedded within his muscles and bones from making up to 700 bricks a day returned swiftly. John joined the project and we spent the next couple of years learning and working together to record and uncover some of the industrial brick making histories.

Brickfield has been lying relatively dormant as a project over the last few years, due to funding issues, as well as having a baby and starting the PhD. However there is hope on the horizon for a new lease of life coming to the project soon, which would mean we could start producing special paver bricks using historic examples as inspiration. Watch this space!

What methods do you follow when collecting and testing materials? Please share any practical tips or steps you take when testing clays and glazes.

To process clay I often sieve it to remove any small stones. This can be done when the clay is dry if outside and wearing a ceramic dust mask. Often with clays gathered directly from the ground they will be quite short, and so the addition of a bit of ball clay tends to help add plasticity. I would always advise people to take lots of notes and be scientific in their approach, though I rarely follow this advice myself and have always learnt by doing, by testing, and retesting until I understand a material, on a physical, material level. If you are testing any materials and have no idea how they will behave, it is a good idea to make small dishes or bowls, as containers to protect the kiln shelves and any other work that might be nearby in the firing.