In Conversation with Natalia Kasprzycka

Describe the place materials play in your work: its locality, place making or place extracting/distilling?

Materials are central to my practice. I consider them to be an expression of place, a tangible piece of matter representing an abstract idea. They can hold so many stories – about geological forces and the distant past we call deep time but also people and their relationship to land.

How does working with these materials, rich with context and labor, impact the outcome of your practice?

The direction of my work is usually dictated by material research and the outcomes vary greatly, from studio pottery to installation to participatory work. Because it’s process, rather than outcome-driven, my practice is open to collaboration and I enjoy working with artists and designers I share an ethos with. What most of my work has in common is its site-specificity – the use of site as a material resource and the communication of site-specific knowledge.

Is it essential to work with local materials rather than purchased ones? How so?

I don’t think it’s essential, nor do I only use found materials. Sourcing and preparing ceramics materials is such a time and labour-intensive process, that if I were to apply it to every single glaze and clay body component I use, I would never have time to make anything! But I do believe that material choices are important, that they need to be informed and relevant within the context of a practice. An engaged relationship with my surroundings happens to be an important part of mine, so collecting and processing materials is a natural consequence of that ethos.

In the UK we are fortunate when it comes to locally mined materials. It’s such a geologically varied island – with some of the world’s oldest rocks in Scotland and some of its youngest on the southeast coast – that a good variety of British ceramics materials are available on the market. My studio relies on a small selection of them, which I add to my collected materials using simple formulae. My rule is to have as few ingredients as possible and only add enough to make my collected materials work in the kiln. I stay away from materials which are likely to have a major carbon footprint or to be unethically mined, which includes most colouring metal oxides. Instead I rely on the palette created by iron oxide, present all around me as clay and rust, or is smaller quantities in ash and some rocks.

What process do you follow when creating – does the material imply the outcome or does it exist alongside an idea?

It’s a combination, really – the material and concept inform each other. Site-specific research is what usually provides context to my work. It’s followed by material investigation which dictates the outcome, an unpredictable process which can be exciting and devastating at the same time. Very often one or more of these parameters is set already and that becomes the starting point.

How the materials interact chemically and conceptually is equally important and I spend a lot of time thinking about how this will be communicated through the work.

Is there a particular project(s) that was/were pivotal in your practice? What has led to material focused work?

I became interested in ceramics as a sustainable practice during my design BA at Camberwell College of Arts. It was the first time I really began to comprehend how objects were being made in a globalised world and I was terrified. Although I now realise it was a bit romanticised, ceramics seemed to offer a way out because it was possible to source one’s materials.

Soon after, during a student exchange programme at Les Beaux-Arts in Marseille, an artist called Delphine Wibaux gifted a piece of clay she’d found to me. That little piece of earth made such an impact that I devoted my semester there to collecting clay samples from across the region. When I realised what diversity of results can come from clays found in one area there was no going back. But it wasn’t until I moved to Stoke-on-Trent and went to Clay College that I was able to really refine this knowledge.

The tile making project at The Exchange, Erith stands out in particular. Would you expand on the role material research plays in this project?

The Exchange commissioned me to create a tile prototype using local materials, which could be produced for the building by a regular group of volunteers. The Exchange building, which is a beautiful former library, is located about 200 metres from the Thames in Erith and we were interested in the properties of the mud from the river bank.It turned out to be the most challenging and rewarding materials I have ever worked with! It took us months of research to get a functional result and I learned plenty in the process.

Although producing tiles was the goal, the outcome in this project was, in a way, secondary. Both myself and the Exchange, who have a strong craft ethos and a real dedication to skill, material and quality, were most of all interested in the potential of getting the community involved in the production from sourcing materials to the end product. Doing the material research collectively was very productive, not just because it allowed us to do the digging, processing and testing on a larger scale – I think people became invested in the process because of how much effort they had to put into making this material they collected themselves into an object fit for their building. They were curious to see it transformed in the kiln. A sense of camaraderie developed in the group, people took ownership of new skills very quickly and passed them between each other, which was especially visible when new members joined the group. For many of them it was their first experience of ceramics but they brought skills from their jobs and passions and found some of them transferable. It’s been a joy working with them all - I have one final session to deliver later this month and I’m sad to think it’s coming to an end!

How would you say the context of working in Stoke-on-Trent has affected your thinking about materials?

Stoke’s history has been dictated by materials. The city was purpose built to mine and manage easily accessible deposits of coal, which in turn fueled local steelworks, thousands of bottle kilns of the ceramics industry and mills which processed imported materials, like bone and flint. Even though much of the industry was gone when I moved here in 2019, the landscape of the city was still its reflection. The slag heaps I walked during the pandemic made me think about the grave contributions we humans make to the material world but I also experienced vibrant life in the same places and realised that nature can thrive more organically in a post-industrial city than in an idyllic countryside setting.

The abundance of easily accessible brownfield land in Stoke created an opportunity to collect and test materials in ways and quantities which I can’t imagine possible in many cities of this size, especially in the UK where land is heavily surveilled. It provided me with a great sense of freedom. In the process, I realised the potential and dangers around using materials from post-industrial sites and began treating them equally to rocks and minerals produced purely through geological forces, following the thinking of the American scientist James Ross Underwood Jr, who campaigned for anthropic or human-made rocks to be recognised as an equal geological category. I was particularly fascinated with blast-furnace slag, which is the waste product from smelting iron.

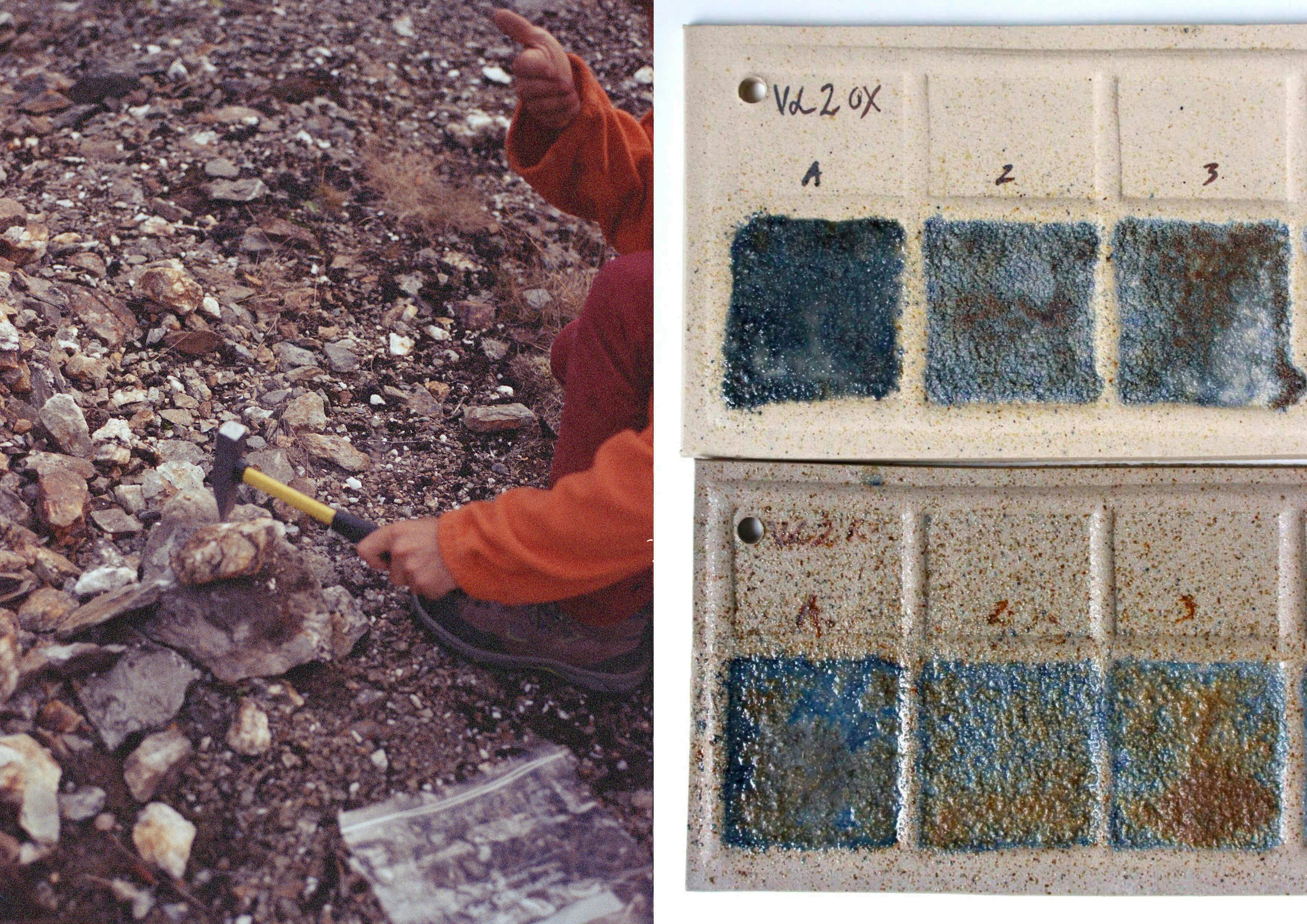

Cobalt Road (2017-21) - mining waste from Wales

What method do you follow when collecting materials/testing? Please share any practical tips, steps you take when testing clays/glazes.

My first guiding rule is doing observation and research before collecting. I use British Geological Survey maps to find out about geology (they have a wonderful online map of the British Isles which is easily accessible on the phone) and Ordnance Survey maps to find routes and traces of industry. I also find that local history websites, often run by very passionate people, are a great source of knowledge. The idea of collecting and firing mystery materials is always enticing, but I think you can potentially prevent some damage to your health and equipment by doing good research!

Photography © Natalia Kasprzycka, Adam Grüning, Lilly Maetzig, Patrik Ontkovic and Glen Stoker.

https://nataliakasprzycka.com/

@natajkasprzycka